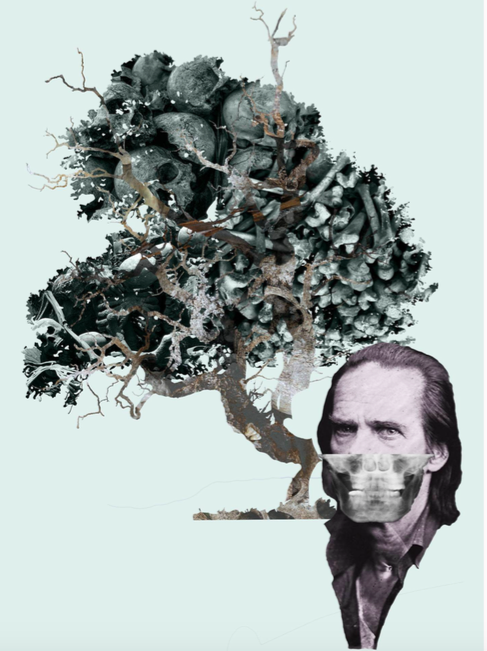

negotiating time and trauma

in nick cave's 'skeleton tree'

By Colin Paton

Time as elastic, time as linear, time as happening all at once in the same moment. In One More Time with Feeling, the documentary chronicling the recording of Nick Cave’s 16th studio album Skeleton Tree, Cave continually grapples with the concept of time. During the recording of the album his 15-year-old son passed away, and both the documentary and the album are centred around dealing with such a crisis. His understanding of the self in relation to the passing of time is dismantled, alongside a similar collapse of any sense of an identity. The album that comes out of this process is a dark, dense and beautiful whole that reflects such an experience of grief. Through a variety of musical facets, it is both striking and complex in the way it presents the experiences of Cave’s trauma.

The album is, therefore, a deeply emotional portrait of loss and trauma. The resulting art from any situation so deeply sad is bound to sting a little sharper than the usual, especially when placed under the scrutiny of a deeply personal two-hour documentary. To listen to the album is to come face to face with the stark, naked realities of such a deep loss. It cannot be overstated how the chorus of I Need You, with its soaring backing vocals rising against the utterly grief-stricken vocals of Cave, works as the sort of musical moment that stops you in your tracks on every listen. It’s an album that stuns simply through its emotional veracity.

However, reducing the value of the album to its sadness does a disservice to the record. It ignores, firstly, that most of the songs were written before the passing of Cave’s son, and though the event absolutely inflects upon the record, there are thoughts and concepts evoked here that were exploring something before simply that of trauma. It also ignores the way in which this music builds such a complex image of this grief. We find in Skeleton Tree a complete musical and lyrical exploration of grief, as opposed to simple a depiction of it. The thoughts found in the film can be found re-packaged in abstract ways throughout the album. Through this context, we are given the rare chance to see how music attempts to navigate specific things: here, I want to focus on Cave’s experience of time.

In Jesus Alone, Cave speaks of calling to someone, constantly refiguring the person or object he’s trying to reach. This begins with the image of a falling body, disturbingly close to an invocation of Cave’s son. Throughout the song, however, it moves further and further away from this specific focus. Gender, race, time and place all flow as one in the search for a companion to sit in the dark with, where Cave builds up a selection of vibrant and beautiful, yet utterly distinct, images. Indeed, in the film Cave notes that a portion of these lyrics are entirely improvised, following simply a feeling in the moment. What connects these thoughts? In such a list of metaphors, defined in their figure only by their disconnected specificity, Cave appears to be calling to imagery itself. It’s a song which yearns for closure, for the coming of a ‘moment’. Over its six minutes of rumination, however, all it can do is aim for some kind of evocation and live in that evocation. We can feel it in the tension of the strings, unable to reach past a single note but thriving in the emotion of that one sound. The moment never comes. The song’s wall of noise drifts out, and Cave is left still calling.

The song is unable to make time continue as it should, stuck in purgatory before ‘the moment’. Musically, the song is defined by its formlessness, with spoken word atop thick, droning waves of sound. It reflects the sense of floating in this time-less void, attempting to find meaning through song, attempting to reach the present, but being unable to. The aforementioned strings cannot get past their note and Cave cannot experience the normal passing of time.

This struggle to negotiate time lives in the corners of the record. It lingers in the barely noticeable yet constantly tapping mechanical percussion behind Magneto; an inescapable reminder of the ticking of the clock, entirely focussed with trying to relive the experience of love in ‘one more time with feeling’. It disorientates through the drumming pattern of I Need You, placing an emphasis on the third beat in the bar and confusing the rhythm in a piece which attempts to find a moment of beauty in the intensity of emotion. It drives the mechanical, claustrophobic percussion in Anthrocene, where Cave muses on a different definition of time: an era. While the melodic pianos attempt to place themselves and slow the rhythm of the song, the insistent drums continue crashing down, just like the constantly moving pressure of time on the lives of humanity and ‘the age of the Anthrocene’. Even in the way Cave sings ‘they told us our Gods would outlive us’ slightly off the beat, in the otherwise sublime Distant Sky, there’s a constant tension in struggling to fit into time. The subject of each of these songs is interlaced with its musical background, forcing us to view them in relation to this negotiation of time. The various ways in which rhythm subverts the music explores the destabilising and disorientating experience of life being constantly and unwillingly propelled forwrd.

The final track, Skeleton Tree, acts as some form of acceptance. He describes how the invocation in Jesus Alone ‘comes back empty’. He finishes the song, and therefore the album, with such mantras of acknowledgement: ‘nothing is for free’ and ‘it’s alright now’. The song is simple and beautiful, with an acoustic guitar strumming throughout, a more usual song structure and a somewhat lack of the overriding tension found elsewhere in the album. There’s a similar acceptance going on musically as there is lyrically, with a return of a more typical sound, structure and, importantly, time coinciding with Cave’s understanding that this is the course his life has taken and there is nothing he can do about it. He accepts the inescapability of time, and attempts to move on. What we hear in the musical acceptance reflects and, indeed, broadens the understanding we can get out of this acceptance of grief. Despite the distinctly lush instrumentation, the song rings of a weariness. Perhaps this is emphasised due to the placement at the end of such an emotionally intense the album, especially when experienced for the first time in the context of a film, but there’s something utterly exhausted in the sound of the song. Something in the way the chords ring and the percussion gently moves along makes it sound as if the whole thing is just about to fall apart but manages to cling on to the rhythm. It depicts Cave’s understanding that he must move along with time, and there is nothing else he can do, but at the same time manages to express the weight of this requirement.

The album is stunning. It’s thick and monochrome, yet also intensely striking. It’s strikingly moving, yet remains grounded and genuine enough to allow it to reach for emotional peaks without appearing saccharine. All this close reading of the music might appear to diminish the simple beauty of songs such as Girl in Amber and Magneto. Allowing ourselves to study the album in this way, however, lets it stand as a statement of artistic vision through music. It combines form with subject to explore both trauma and song writing in a subtle and prescient way. It allows us to explore Cave’s distressing inability to comprehend time in relation to the depths of grief.