Making Waves: Immaculate (2024) by Will Bates

By Aidan Monks

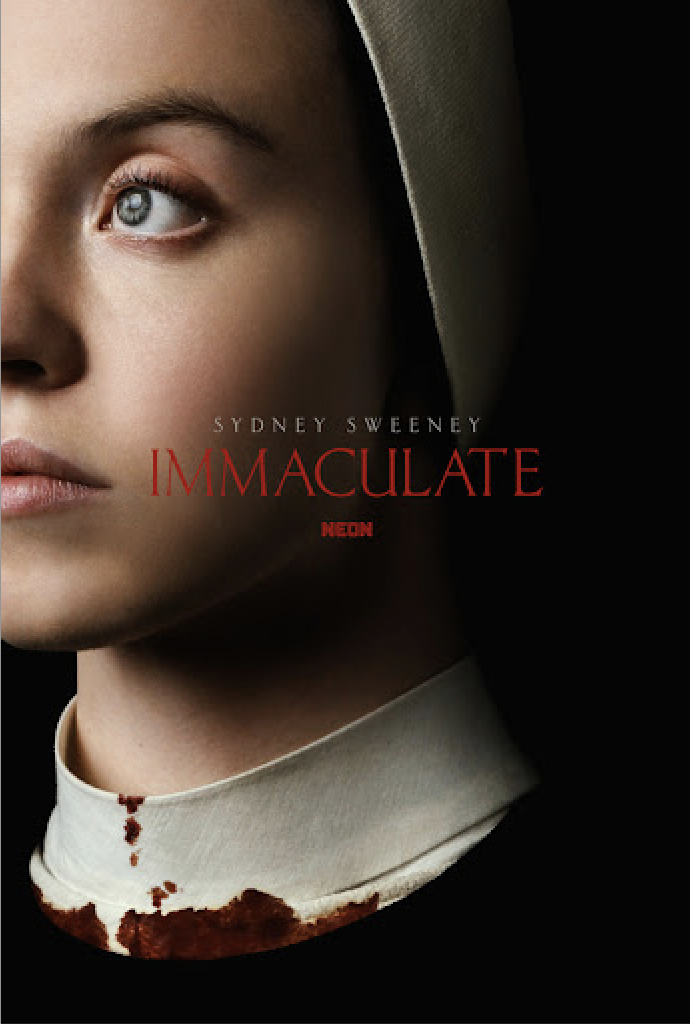

There is no way of reviewing the soundtrack of this film without first exploring its substance. Sydney Sweeney’s near-decade spanning passion project has released to predictably lukewarm reviews (with a weighted average of 56% on Metacritic). However, in a more surprising turn of events, Immaculate has made only ripples in the film industry and the cultural sphere which recently exalted Sweeney as the Gen Z scream queen. Perhaps we can credit this with the burnout climate of post-awards season Hollywood, or the commercial genre revival Anyone but You (also fronted by Sweeney) overshadowing her subsequent steps, or maybe the movie is just plain bad.

I’ll be blunt: Immaculate is a mediocre film, sometimes brilliant, occasionally awful, sometimes smart, and equally stupid. Rotten Tomatoes offers a critical consensus with a mildly irritating pun from the get-go: “Immaculate in conception if not always in execution…” Unfortunately, this is true. There are cerebral concepts at work, especially in the first two thirds of the film, which are, for the most part, treated creatively. Cut to the sixty-minute mark (the film is only 1.5 hours). After a belated plot twist and an uninspired segment of last-act exposition, viewers can surely concur that Sydney Sweeney’s latest opus in genre filmmaking is a bona fide Almost Got ‘Em.

That said, there are certainly debates to be had about the film’s aesthetic and political merits. Like most generic horror movies today, Immaculate stands on the shoulders of a vast and lengthy tradition - in this case, the cinemas of religious repression, maternal angst, and institutional abuse. The film follows Sister Cecilia, a devout nun from Detroit, who joins a convent in rural Italy on personal invitation from Father Tedeschi; a few months and nightmarish interactions later, Cecilia, a virgin, discovers that she is pregnant. Get it? Naturally, there is a debt to Rosemary’s Baby which frames themes of superstition and divine paranoia through the discourse of male violence. Immaculate attempts to do this, if not more obviously.

But the most obvious comparisons which may - and should - be invoked are with ‘nun movies’ since the 1940s. I am not talking about The Conjuring spin-offs. Films like Powell and Pressberger’s Black Narcissus or The Devils or even Verhoeven’s erotic thriller Benedetta, which playfully tackles the tragedies and comedies of sexual liberty in a time of clerical repression. These movies are similarly metaphoric, employing the backdrop of Catholicism and psychology of silence to create unease. Immaculate is less compelling than any of these entries because it leaves far less to interpret. But that does not mean it does not punctually dramatise the pressing political emergencies of maternity, pregnancy, and the rights of the mother by posing very serious questions in the most significant election year of our lives. On a political front, the film merits attention.

Now, the score.

Composer Will Bates, a relative newcomer, has composed music for several TV unknowns as well as a couple of successful video games and underground genre films. Bates’ work on the GameStop biopic Dumb Money in 2023 went as unnoticed as the film itself, which features another exceptional performance from Paul Dano. Immaculate is Bates’ first mainstream composition, and possibly the first for which he will receive critical recognition - it is the only consistent (dare I say… immaculate) aspect of the film. David Lynch often reminds us that sound makes up at least 50% of film form. But in the case of horror, in the act of suspense or creating mood, it arguably accounts for much more - including all elements of sonic design, music being one of the pre-eminent players. Wherever the dialogue or direction of Immaculate falls short, the score manages to extract the terror of expectations - of jump scares, etc. - and provide a compelling tonal character when (e.g.) Sweeney’s acting lacks the lustre necessary for the upkeep of tension. Sometimes a good score is undetectable, but sometimes it is the invisible protagonist whose performance elevates a film from mediocrity.

From the opening bars, Bates envelops audiences in a world of pomp, piety, and grandeur with Baroque strings weaving shapes and patterns around the Screen 2 auditorium on ‘Our Lady Of Atonement’ - assuming you are watching the film in the NPH - and polyphonic vocals dictating Latin on ‘Sister Cecilia’ as if arranging the Tridentine Mass into a melody. Indeed, this is the protagonist’s leitmotif in every sense: it plays at key moments, transitions and transposes with Cecilia’s development. It is also worth noting that the vocals are uniquely female soprano, which has certain implications considering the central themes of female oppression within the church and, ultimately, overcoming. The environment which Bates initially places us in is fiercely ritualistic, steeped in the toils of history and ceremony. But the score is - like the dreaded convent - not as simple as first glance portrays.

Harpsichords and broken pianos murmur in the dark passages and catacombs which Cecilia navigates by day and night, usually in minor keys and accompanied by a distinct singular or two-note pulsating drum beat (‘Death Is A Part of Everyday Life Here’) to eerie effect. The tone is congruous. Something is not right, or is not known to Cecila (us) and is thus out of her control - there are forces at work rendering her vulnerable. The element of the unknown is what prompts the feeling of terror, along with the subconscious desire to know, and Bates’ uncanny soundscapes reinforce this if they do not generate it themselves. In many ways, Sweeney’s Cecilia succumbs to the Gothic stereotype of the vulnerable young woman wandering a dark and dangerous estate with no knowledge of the monsters unseen. Although, of course, these monsters are neither transhuman or supernatural. Without spoiling anything, I will say they are physical, carnate, material, masquerading as divine. Therefore, the ruptured piano’s echoing notes take on a dual meaning. They simultaneously ground the ‘evil’ assailing Cecilia in the earthy sound of the piano’s material, physically hurt as her own body is similarly imperilled by the clergy, and create an equally immaterial, oneiric sound effect with an out-of-body denotation. This is amplified by significations of the piano’s brokenness, its once-completeness. In simpler words, the spiritual noise is something of the past, long gone and beaten by the actions of physical bodies. Immaculate is - for better or worse - an anti-religious movie in every way, and this aspect of Bates’ score is undeniable.

As if wrapping his creative product in a neatly ironic bow, Bates caps off the Immaculate score with a bizarre rendition of Schubert’s ‘Ave Maria’ with a baseline backing the melodious choir played on (what sounds like) a marimba before an unexpected turn featuring some light brass around the halfway point. This two-minute absurdity plays as the credits scroll, following what I am confident will be one of the most jarring endings to a film this year. Bates makes us sit with the contents, feel the extremities, the contradictions, and all the post-splatter shock factor. The result is eeriness dealt with a self-reflexive and satisfied blow. Despite the film’s arrhythmic genre-bending and questionable structural choices, Bates’ score finds unifying motifs in the particulars and attempts to consolidate the overall; whether he achieves this in a film as convoluted and stylistically derivative as Immaculate is up for debate. But, as far as Will Bates is concerned, perhaps this work will finally put him on the map.