Enka: the imagined homeland

By Ilene Krall

DREAMS

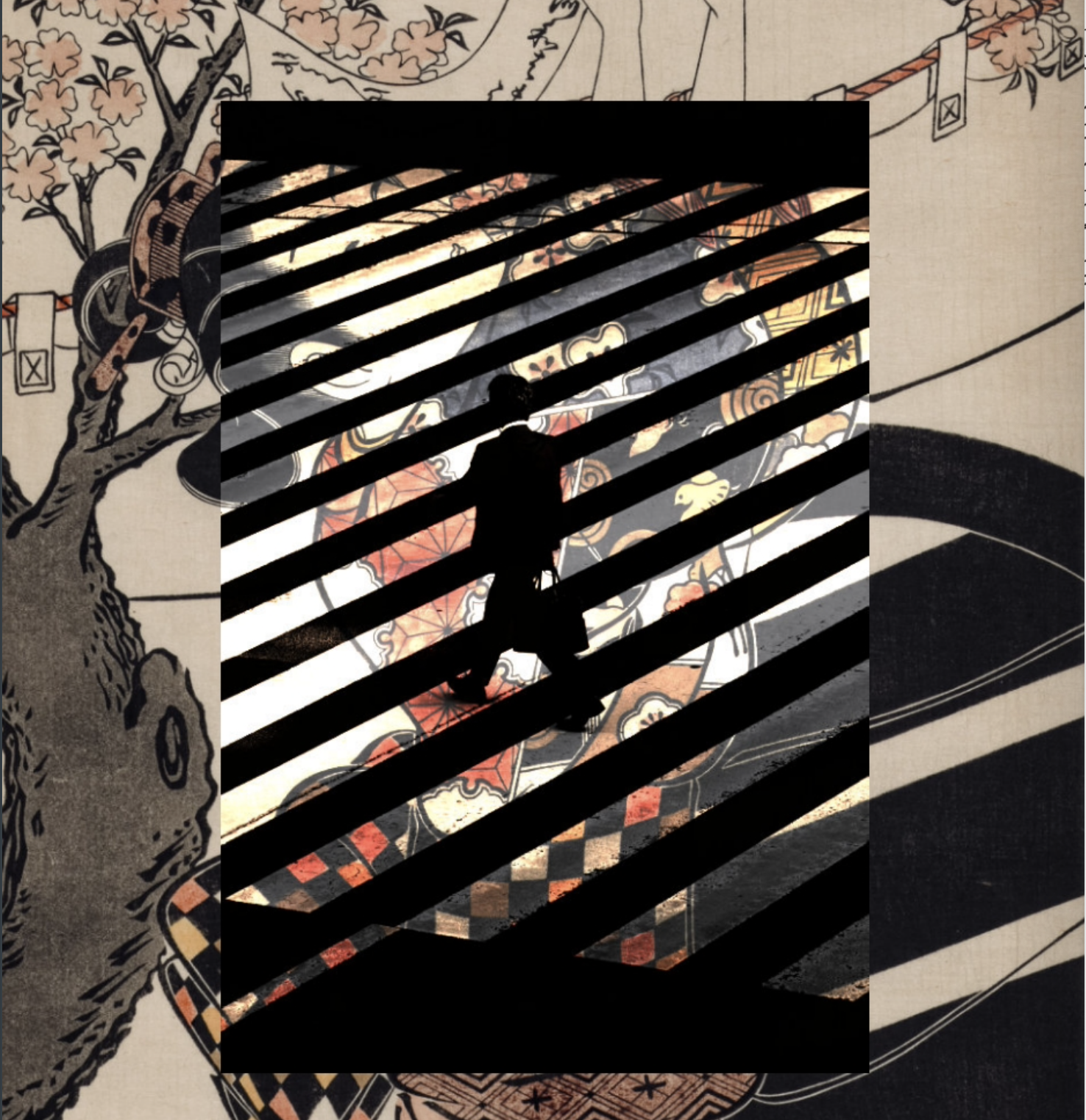

Hanging Poems on a Cherry Tree, Library of Congress, Ishikawa Toyonobu, 1741

Unknown, Arielle Friedlander, Auckland, New Zealand, 2023

Composting: Jack Sloop, January 2023

As I fold my knees on the soft tatami of my grandparents’ living room, the perpetually running TV plays a performance of a pale woman with dark hair in a kimono, her powerful vibrato running against grandiose backing music. The singer belts out a popular enka song. Though it may be unfamiliar to foreign ears, my Japanese grandparents frequently play enka music throughout the house, making sure my brother and I grow up with the music they enjoy and hope to pass on.

Enka, a genre of music endemic to Japan, speaks of the kokoro, or soul, of Japan. Its lyrics paint pictures of Japan’s rolling mountains, green fields, and sprawling blue oceans. Its themes speak of devotion to the furusatō, or the homeland, and of yearning for love, friendship, and loyalty. Emerging in the late 1960s, enka underscored the angst of a destabilised post-war generation that sought to reconnect with the collective conception of their homeland.

For the Japanese (and I speak from experience), being deemed ‘truly’ Japanese is of great importance. The music you listen to, the food you eat, and the people you spend your time with all indicate how Japanese you are. ‘Japaneseness’ is earned through devotion to the homeland, and loyalty and respect for tradition are key aspects of earning this label. So, during an era of widespread alienation, younger generations sought to reground themselves to their identity by returning to the traditional. Enka emerged in this context, subverting expectations of younger generations to distinguish themselves from older generations through novel music trends. The emergence of enka thus foregrounded the “introspection boom” of the post-war era, where Japanese society fixated on the question: “Who are we Japanese?” By evoking images of rural Japan, a long-lost lover, or the breathtaking beauty of Japan’s nature, enka evoked a sense of nostalgia that allowed the Japanese public to feel connected to their homeland once again. A need for community, and enka’s ability to fulfil this yearning, “suggests a forum for collective nostalgia,” writes Christine Yano, “which actively appropriates and shapes the past, thereby binding the group together.” As a result, enka becomes a tool to create and reshape Japanese identity.

The homeland enka captures, however, is imagined and produced. Specific characteristics of enka reinforce its reputation of authenticity, while others hint at its international roots. The genre’s predecessors, kayo ̄kyoku or ryu ̄ko ̄k, are a primary indicator of enka’s non-Japanese beginnings. The genres, which emerged in the 1940s, are heavily influenced by jazz and blues. Western music, first introduced to Japan at the start of the Meiji period (1868) according to Deborah Shamoon in her 2013 article ‘Recreating traditional music in postwar Japan: a prehistory of enka’, was quickly accepted into the country, and mastery of its techniques was considered crucial to the modernisation of Japan. Jazz grew steadily in influence and, by the 1940’s, was merged with kayo ̄kyoku to create a fusion genre popular with younger audiences. Products of this fusion genre influence enka.

An example of this fusion is the emergence of the pentatonic scale. Much of popular Western music is based on the seven-note scale. Traditionally Japanese music, however, was often based on three note tetrachords. According to Shamoon, “composers in the Meiji period, in an attempt to fit these older modes into Western classical music theory, incorrectly described them as pentatonic.” Thereafter, pentatonic scales were utilised throughout Japanese music and incorrectly labelled as traditionally Japanese. Titled yonanuki cho ̄-onkai (pentatonic major) and yonanuki tan’onkai (pentatonic minor), these scales were used as indicators of authentic Japanese music, though their origins suggest otherwise.

Other hybrid features taint the perception of enka as an authentically traditional genre. Vocally for instance, as Gaute Hellås explained in 2012, enka is sung utilising traditionally japanese vocal styles and techniques. One popular example is that of ko-bushi, which Hellås defines as “vibrato-like ornamentation that can produce an effect which resembles stylized crying.” Paired with themes of longing, heartbreak, and love, this style of singing heightens the song’s emotional impact. Techniques which are not traditionally Japanese, however, are also employed. Yuri, more similar to Euro-American vibrato techniques, is used in some enka tracks, evoking a “distinctive ‘swinging’ of the voice.”

Structurally and thematically, enka is highly repetitive. According to Hellås, the repetitive nature of the genre “imprints a set of musical expectations and familiarities over time.” This allows audiences to set aside curiosity and listen to enka for what they believe it is: an evocation of the furusatō. The genre thus relies almost completely on emotional appeal, intensifying its impact and tightening its relationship with audiences. Enka’s general commitment to the poetic features of Waka also aids in this emotional connection to audiences. Waka consists of three verses of five to eight lines, each of which are made up of five to seven syllables. These lines utilise “emotional lyricism expressing beauty and sadness often through use of images of nature and elements of nihonjin-ron, the theory that Japan is culturally and linguistically unique and pure,” according to Hellås. Carrying these poetic features through to enka, the genre’s seeming commitment to the furusatō is heightened, furthering audience perception of enka’s authenticity.

Performative techniques are also utilised in order to evoke a ‘traditional’ Japan. Enka performance is highly ritualised. Singers often perform in traditional Japanese kimono, accompanying ballads that describe the performer’s Japan with pronounced vocal ornamentation and intense orchestration. Each of these characteristics of the genre serves to establish music that evokes a feeling of nostalgia and belonging.

If enka’s image of authenticity is false, however, what does that mean for enka’s impact as a tool to create a collective, imagined homeland? The importance of tradition in Japanese culture is reinforced in many ways, particularly through the cultural fixation on imitation versus authenticity. Would you prefer a hamburger over ramen? Ah, not very Japanese, are you. Do you prefer rap to enka? Oh, so you’re not really Japanese then. Simple distinctions such as these often hold relevance in someone’s perception of one’s Japaneseness. But, when enka, an indicator of Japaneseness itself, can be proven to be not completely, authentically Japanese, what does that imply about the concept of true Japaneseness?

Though these questions cannot be answered in this space of this article, enka’s role in eliciting the collective imagined Japanese identity speaks volumes on music’s ability to unite a group of people. As a cultural tool, enka provides a common ground for now older generations of Japanese to feel more connected to the furusatō, and remind them of the Japan that they believe once existed.

By always having enka blaring from the TV, my grandparents passed on not only a love for a genre that has been quite contained to a single culture, but also the nostalgia of the kokoro of Japan. Despite its hybrid origins, enka’s reputation as authentic and honouring the furusatō is more impactful, keeping its role as a cultural unifier intact. Do the origins of a genre or piece of music indicate its impact? Are origins truly important? Though beginnings may be important in a technical sense, such as per the musical makeup of enka, I believe they are ultimately secondary to perception. Enka is perceived as traditionally Japanese, and so it is. Despite my mixed heritage, my family has raised me to be Japanese, and so I am. In our similarly hybrid roots, I feel a connection to enka unmatched by other music genres, and I know it will be blaring out of my TV when I have grandchildren of my own.

Shamoon, D. (2014), ‘Recreating traditional music in postwar Japan: a prehistory of enka’, Japan Forum, 26 (1), pp. 113-138.

Yano, C. R. (2003), Tears of Longing: Nostalgia and the Nation in Japanese Popular Song, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center.

Hellås, G. (2012), ‘Changes in a Changeless World: Continuity and Discontinuity in Japanese Enka Music’, Master thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo.