Emotional expression in times of conservatism: slowdive in the 90s

By Owain Williams

‘... But I was there.’

On LCD Soundsystem’s debut single, ‘Losing My Edge’, frontman James Murphy mocks the “art school Brooklynites” with their “little jackets” and their “borrowed nostalgia for the unremembered 80s”. While, unlike Murphy, I was not there - and deep down wish my notalgia was a tad more authentic - I can’t imagine anyone forgetting the sounds and sonic experimentation born from that era. We had Bruce Springsteen hitting his stride, Kate Bush running in the night, The Jesus and Mary Chain’s “Just Like Honey” serving as my dad’s go-to last dance song back in his DJing hayday, Sonic Youth getting everyone a-riot - you could go on. The latter two especially, on the shoulders of the post punk movement, laid the foundations for a fuzzier and less structured sound which contemporaries like the Cocteau Twins and My Bloody Valentine would further flesh out at the turn of the 90s. Adjacent was the Acid House movement, embracing hedonism and promiscuity, and fostering an egalitarian community for people of all genders, sexualities, and races.

This music wasn’t afraid to be emotional, and the musicians themselves were at times overtly political, necessitated by the political atmosphere in Britain in their time. The experimentation of shoegaze was born from the dissolution of 80s Britain under Thatcher, and the communities built within Acid House stood in direct resistance to her government’s broad and scathing cultural conservatism. The despondency felt throughout Britain had to be challenged. People needed an outlet to feel again, whether through Acid House’s escapism or shoegaze’s emotion.

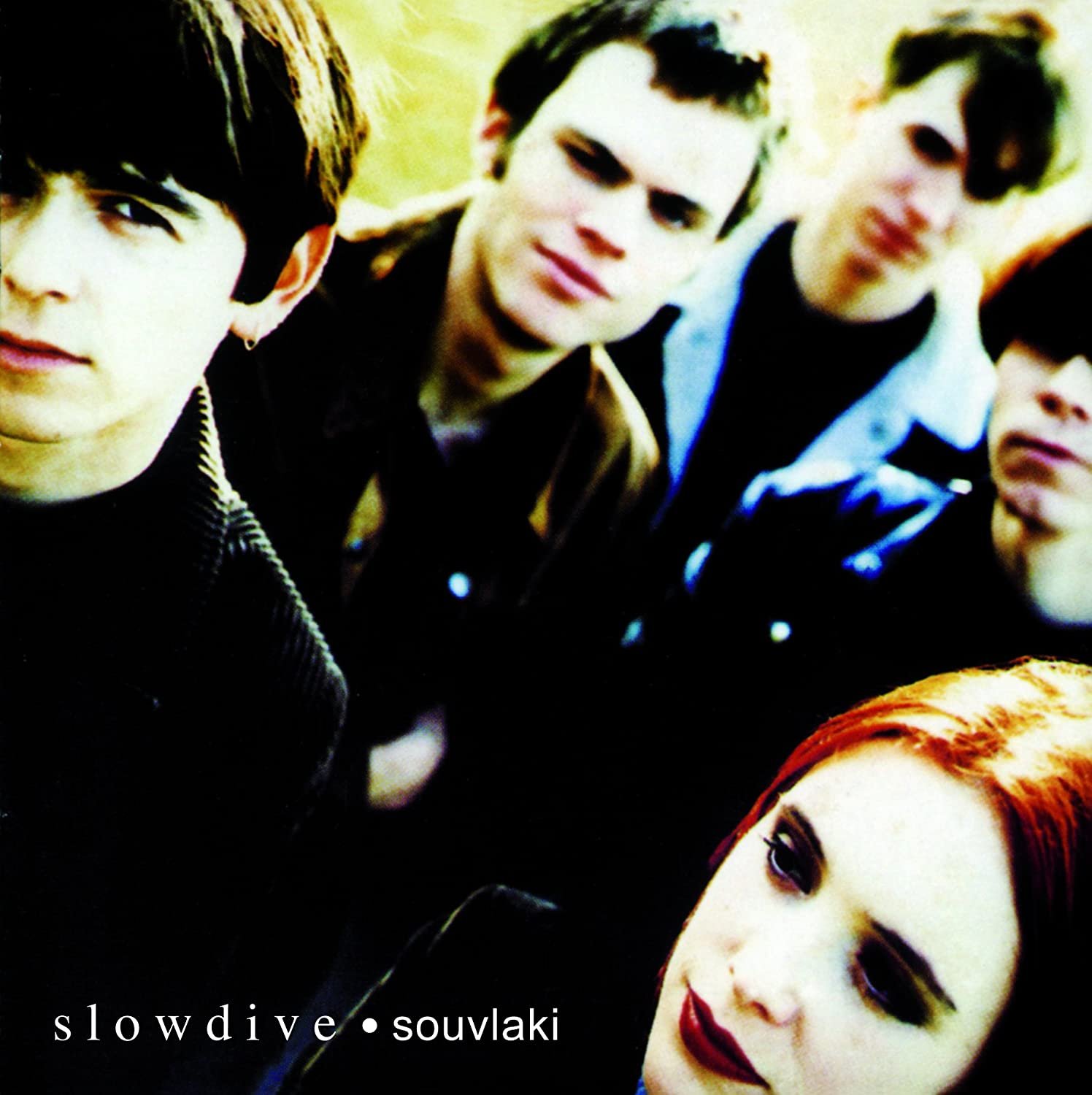

Somewhere in the mix, four hopefuls from Reading, led by Neil Halstead and going by the name of Slowdive, sought to make a name for themselves. Just entering their 20s, they’d signed a deal and released an EP. In 1991, they followed it with Just for a Day, a record oozing with a sweet atmosphere amid dizzying guitars. For a first effort, it was reviewed well by some: Simon Williams at NME called it a “fine, fragrant affair”. Yet it was criticised by many more for falling too closely in line with other shoegaze bands of that era: Melody Maker’s Paul Lester dismissing it as a “major fucking letdown”. Crikey. Although it dampened spirits at the time, the band had a point to prove and more to experiment with, and so began the recording of their followup: Souvlaki.

The Perfect Recipe

When creating a buzz about an album, it can easily feel contrived. Sometimes you have to exaggerate the dynamics of the band, the tensions, the breakdowns in the studio, what’s on the line if things go wrong. With Souvlaki, there was no need to exaggerate anything - every trope was already there beat by beat. Frontman Neil Halstead & vocalist Rachel Goswell had been longtime partners after being childhood friends; from learning guitar together through to forming the band, their dynamic was central to the band’s presence. This was all up until the early stages of recording the new record when they announced their split. Their separation tore through the band, but they did their best to get through it. They kept touring, but it was impossible not to fracture somewhat. When it was time to continue recording, their whole identity felt as good as lost. Would the band collapse and wither out of relevance with only two half baked releases to their name?

You’d hope not. And luckily, no spoilers, this wasn’t quite the case. Eventually, after upwards of thirty songs being rejected by the label, Halstead was pushed - upon his manager’s recommendation - into an isolated cottage in North Wales for weeks as a last ditch attempt to reforge any kind of creative identity. Soon enough, he emerged with the skeletons of what would become ‘40 Days’, ‘Machine Gun’ and ‘Dagger’ - three of the most predictably depressing tracks off the final release, locking you in emotionally, holding you down with their dense, luscious atmosphere until each track’s end.

Having breathed some air into the recording, it was time to begin production where they somehow bagged Brian Eno to produce the airy ‘Sing’ as well as ‘Here She Comes’. This was after he refused to commit to the entire project, but his help on these songs broadened the band’s electronic music palette, with Halstead admitting to taking influence from Aphex Twin for the song ‘Souvlaki Space Station’ . Either way, with such a big name helping out, things were going well, although Goswell and Halstead’s separation was simmering up through the songwriting - Halstead’s ‘Dagger’, the most stripped backed cut off the LP, details their toxic downward spiral, and Goswell’s ‘Souvlaki Space Station’ features cryptic lyrics that Halstead still refuses to decipher today.

So far, we’ve the two leading members breaking up in the first weeks of recording, the subsequent near break up of the entire band, two issues which only seem to have been resolved with the sensible solution of locking up the grieving frontman away in the North Walean countryside for weeks on end until something stuck. This, coupled with the touch of Eno, had the album ready and the band raring for its 1993 release. A wild ride, maybe the perfect recipe for the finest ‘Souvlaki’.

Falling & Laughing

It could be said that critics thought otherwise. Upon the album's release, Melody Maker’s Dave Simpson remarked, “I would rather drown choking in a bath full of porridge than ever listen to it again”. Nice. It was almost universally panned, coined “out of time, out of mind & out of fashion”. This quote is the most telling. To understand how an album so widely acclaimed twenty-odd years down the line could have been scolded this much upon release requires one to understand the broader themes of the time, both within the label and in British society.

Slowdive was signed to Creation Records - the same label which boasted The Jesus and Mary Chain and Primal Scream - led by Alan McGee. Since their inception in the early 80s they’d made the principled commitment to remaining independent, to cut through the corporate rungs and get straight into signing. They sought to sign what was fresh, what would take other label’s years to get pressed on vinyl. It worked music-wise, and the label was influential in helping spread some of the most exciting sounds from Glasgow and beyond, but their records were not commercial superstars. Debts accumulated, and in 1991 Creation was forced to sell to Sony. Two years went by, and one night McGee missed his train from Glasgow to Manchester and stumbled into King Tut’s where a small band from Manchester, going by the name Oasis, happened to be playing. McGee told an onlooker at the gig, “I’ve found the band that’s gonna save the label”. He was definitely right, but this did no favours for Slowdive.

This signalled a shift in both sound and direction for the label; after years of delving into acid house, they’d suddenly helped birth Britpop, and it was selling. The corporate attitudes they’d been avoiding for nearly a decade were now there and in full swing. They couldn’t get away with letting a band bankrupt the label for two years to produce an album, as had happened from ‘89 to ‘91 with My Bloody Valentine’s ‘Loveless’. The music came first then - it couldn’t afford to now. The internal politics were set, and just over a year later, Slowdive were dropped from Creation.

Back to Basics

Beyond the scope of Creation, British culture was increasingly shifting towards rekindling a sense of identity. The rampant privatisation under Thatcher in the 80s, along with the dismantling of unions, dissolved the fabric of Britain’s urban hubs, instilling an ever-growing discontent among residents. As alluded to, Acid House and other similar movements provided outlets for young people in particular. Paradoxically, as the scene expanded, it attracted unbridled entrepreneurship (strongly resembling the economic libertarianism central to Thatcherism). But its cultural acceptance of minorities, sexuality, immigrants, drug culture, and promiscuity sat too far in contradiction with conservatism, resulting in police crackdowns of the scene, culminating in the banning of outdoor raves in the mid-90s under John Major.

This expansion of police powers coincided with Major’s push to go “back to basics”: to embrace the family and to reject the growing social diversity within Britain. Although rave music found ways to resurface, permeating culture through to the present day, the state agenda was set. Protests against these policies were not supported by either dominating political party, as Labour wanted to capture a so-called sensible central position. The genre was commercially stigmatised. Sony pressured Creation to move from Acid House, to find the moneymakers and to “Roll With It”. Oasis represented a Britishness which could be universally accepted - and that fell in line with broader state interests.

The Britpop sound encapsulated “back to basics”, rejecting the sonic experimentation from the late 70s through to the turn of the 90s and rehashing the best of the 60s. The previous ten years had been awful for most people, so why not just forget they ever happened? Best of all, Britpop remained almost entirely apolitical, and with the exception of Pulp’s discography, would only ever go as far as calling the rich a little out of touch (‘Charmless Man’ by Blur). It was devoid of emotion, embodying the attitude to just suck it up and carry on: masculine in the worst way. Its attitude felt countercultural, but its substance remained diluted - defining the success of the movement by records sold and rivalry (Blur vs. Oasis) rather than a broader impact on music. It echoed the sounds of the 60s - an era of radical thought infused with the birth of modern music as we know it - but trimmed the former entirely, leaving only the melodic husk. Britpop was a corporate bastardisation of alternative culture and an assimilation into neoliberalism, but the British critics loved it.

The Real NME

To them, music had grown too emotional and depressing, and abroad in America these themes were growing ever stronger with the advent of grunge, making even the heaviest of music kill your mood. Rather than accepting this emotion as a valid form of expression which reflected many people’s growing despondence, they were reactionary, rejecting it completely. Perhaps they felt just avoiding the problem might make it go away forever. Total apathy. Britpop bands challenged this trend, and so the media narrative was established. “Yanks go home!” stated the cover of a 1993 Select magazine - a manufactured narrative that these bands existed solely to challenge America. Defend your Britishness by listening to Britpop today!

This brings us back to Slowdive. They embodied all of the emotional and experimental traits the music press had grown tired of, with even the most independent of outlets like Melody Maker’s distaste aligned with corporate interest. Caught in the moodier corner of this contrived divide between grunge and britpop, the writing was on the wall. Interestingly, other bands at the time also derided shoegaze, with the Manic Street Preachers’ Richey declaring, “I hate Slowdive more than Hitler”. Thehe Manics’ music was some of the most politically radical of the era. They were victims of the same apolitical cultural dominance as Slowdive: they were too political, while Slowdive too emotional. It’s not that Britpop was particularly awful musically, but its existence forced so much more interesting and challenging music to the wayside. As Ride’s lead, Mark Gardener, put it: “Britpop Killed Experimental Music”.

Rebirth & Repetition

Since the 90s, music has continued to change. The internet’s influence in the spread of ideas and rediscovery of music cannot be understated, and Slowdive have been lucky in this regard. In their era, the music media had massive influence upon sales and public perception. They could manufacture narratives and kill off genres as they nearly did with shoegaze. But today, the diversity of readily available opinions and the decline in readership for many of these publications has weakened the media’s influence. Additionally, the emergence of dream pop bands such as Beach House has exposed a new generation of listeners to a similar sound, encouraging people to look back on their influences and unearth bands such as Slowdive, Chapterhouse, and beyond. Today, Slowdive are considered one of the greatest bands of the 90s, and have since reformed and released their most successful album to date.

In terms of Britpop, now the dust has settled, many of the artists now reject what the movement represented. Suede’s Brett Anderson described Britpop’s “core politics as anachronistically patriarchal and, actually, borderline toxic”, and the lead of Gene said “I’m slightly ashamed… I didn’t see it for what it was - a return to white, male dominated Britain.” Their reflections demonstrate an awareness we ought to sustain today as we find ourselves in times of similarly sweeping cultural conservatism amid expansion of police powers and a decade of crippling austerity. The seeds are sown for the re-emergence of the 90s’ apathy and dissolution, and with that I hope the bands of today do not share the experiences of Slowdive in producing exciting and emotive art. The rejection of Britpop by two of its pioneers affirms this hope. One movement stood the test of time; the other dwindled.