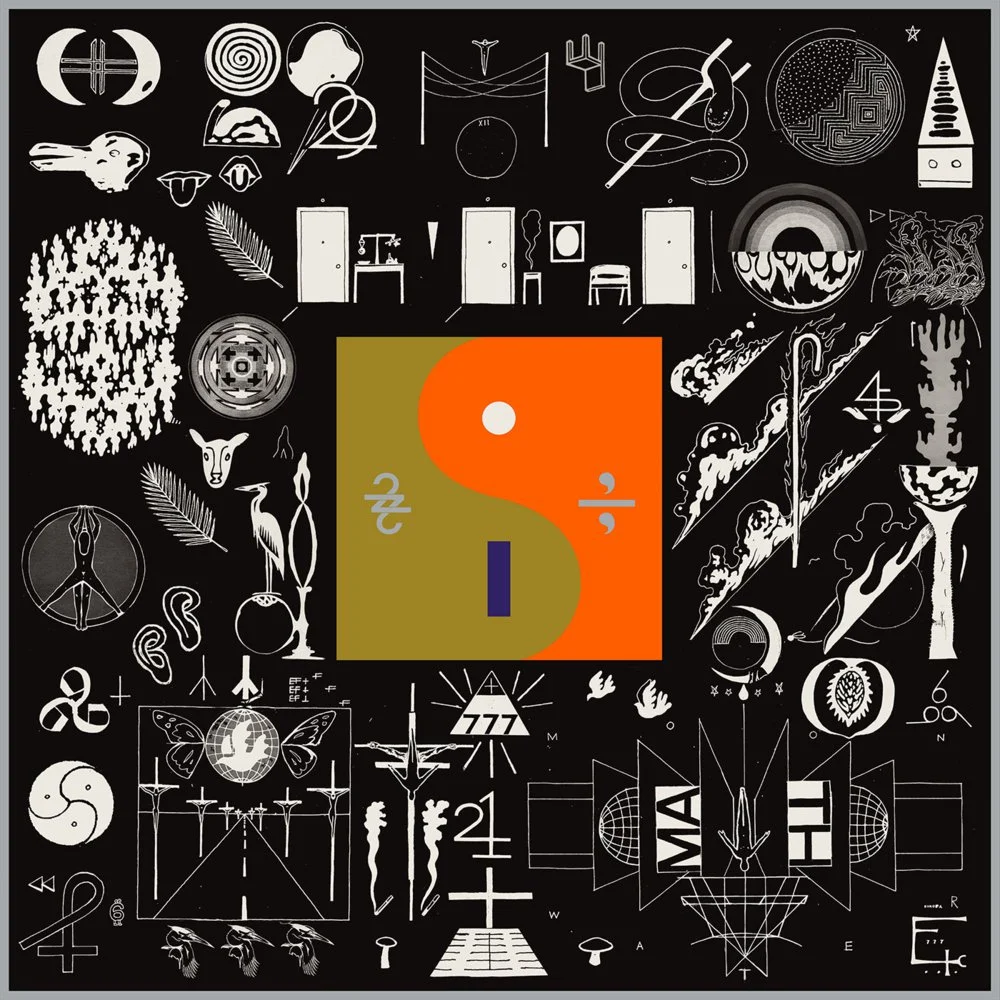

bon iver: 22, a million - review

Words by Maddy Bazil

Bon Iver’s debut album, 2007’s For Emma, Forever Ago, is grounded in earth. It has a corporeal form; it charts Justin Vernon’s deep sadness and isolation following a breakup with his girlfriend and a breakup with his band. The tale of the album’s conception in the depths of a Wisconsin winter has by now been mythologised. For Emma is about relationships, about the loneliness of solitude, about nature’s power to restore. It is intensely relatable and intensely human. Its follow-up, 2011’s self-titled Bon Iver is transcendent. Centred around the notion of place, it nonetheless feels ethereal, more about intangible places - memories, moments - than geographic ones. Musically, it takes Vernon’s falsetto and folk strumming and transforms it into a world of sweeping cinematic soundscapes. Less solitary, more all-encompassing, the album gives you the sensation of a celestial storm cloud blowing in.

If For Emma, Forever Ago is earth, and Bon Iver is sky - well, the outfit’s long-awaited third album, 22, A Million, seems at times to have been beamed to us from the far reaches of the solar system.

The first track, 22 (Over S∞∞N), opens and closes with Vernon’s distorted, alien-esque voice intoning the cryptic words ‘It might be over soon’. Achieved using the ‘Messina’ machine, a vocoder device created for the album by sound engineer Chris Messina, the effect is haunting - an immortal-sounding voice reminding us, for better or for worse, of our own mortality.

Throughout the album, Vernon continues to play with sonic textures and opaque lyricism in what at times feels like an attempt to shake off any folksy For Emma fans still sticking around despite it all. 10 d E A T h b R E a s T ⚄ ⚄’s pounding synthesised rhythm peters off abruptly, intermittently, into moments of harmonic vocals and buzzing static. Yet it isn’t all dissonance and newness: 715 - CRΣΣKS is quietly elegant, its spareness reminiscent of 2009’s elegiac Woods.

Part of the beauty of Bon Iver’s music has always been its lyrical poeticism. Vernon’s writing is autological and sound-conscious, and despite - or perhaps as a result of - their lyrical opacity, his words feel universally relatable in their emotion. Most glorious are the moments of clarity which are thrown into relief against this misty veil. At 1:25 in 33 “God”, Vernon yelps out the line ‘Stayed at the Ace Hotel’, and it feels like we are blinded by dazzling sunlight, briefly returned to the (relatively) earthly realm that is Los Angeles. Or take 3:25 in 29 #Strafford APTS, where Vernon’s impenetrable, distorted, falsetto cracks just the tiniest amount in a blip of static on the heartbreaking phrase ‘alimony butterflies’, and all of a sudden he is human again.

And it is this dichotomy between man and machine, between natural and artificial, between earthly and heavenly, which is at the heart of the entirety of 22, A Million. Where For Emma was about interpersonal relationships and Bon Iver was about geographical relationships, 22, A Million sees Vernon reckoning with the most fundamental subject of all: the human condition, explored through the context of religion. The album is rife with mentions of consecration, confirmation, God. 22, A Million feels at various times to be one part confessional, one part 95 Theses, one part hallelujah choir.

It is an album of being abandoned in the reeds (715 - CRΣΣKS). It is an album of heresy (666 ʇ). It is an album of fear and anxiety (‘Well I been caught in fire / I stayed down / Without knowing what the truth is,’ confesses Vernon in the track _ _ _ _ 45 _ _ _ _ _ ). It is an album of feeling forsaken (‘Why are you so far from saving me?’ asks 33 “God”, in a desperate, aching echo of Psalm 22).

But it is also an album of atoning and moving on (8 (circle)), of finding a new wholeness (‘Now I’m more / Than I am when we started’ ends 21 M♢♢N WATER). The cyclical, soothing, closing track, 00000 Million, rejects the theological turmoil of the songs prior - ‘A word about Gnosis: it ain’t gonna buy the groceries’ - as well as rejecting that which was previously haunting: ‘I worried bout rain and I worried bout lightning / But I watched them off, to the light of the morning’.

00000 Million samples Fionn Regan softly repeating the line ‘The days have no numbers’. After an entire album spent defining places, moments, experiences by a mystical divination of significant numerologies, this feels like a clean break. 34 revelatory minutes later, in the stark and beautiful universe of Bon Iver, a roiling night has ended. Finally, morning has broken.