benjamin clementine & ala.ni @ somerset house, london

Words by Olga Loza and Lara Johnson-Wheeler

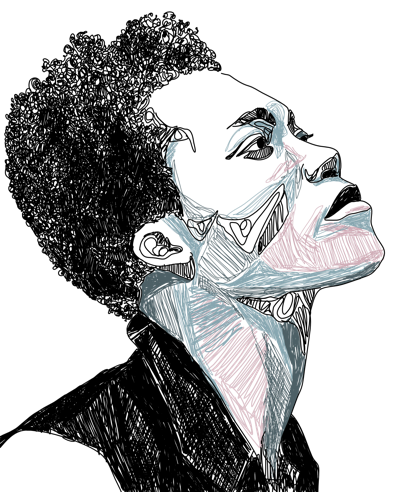

London-born Benjamin Saint-Clémentine, known simply as Benjamin Clementine, is said to have been basking in Paris, barefoot, when he was discovered. Of course he was: it’s so easy to conjure an image of him, tall and slender, with a look that’s in equal parts rough and groomed, gliding through the streets of Paris, singing. Since his Parisian youth, he debuted at Later With Jools Holland in 2013, a performance which sparked off a dynamic career that culminated in winning the Mercury Prize in 2015 with his debut album, At Least For Now.

OL: I first got acquainted with Benjamin Clementine’s music when I moved to London. The dark melody of the song he devoted to the city resonated with my splintered heart’s concerns and anxieties: “Transcending the barriers of / Yesterday was and is the dream,” I hummed along with his voice, viscous like liquorish, on my morning commute. I could not miss his live performance, I needed to see him stand on the stage in front of a crowd to confirm his corporeality, his physical existence.

On the day of the event, the air was stagnant and humid, the sky overcast, and London seemed too crowded: as we navigated our way through Soho to Somerset House, I felt vaguely faint, dazed by the mercurial movement of an amorphous crowd, seizing Lara’s hand as she confidently glided through the streets. I hadn’t been to Somerset House before, and to me it seemed majestic—a glorious and ornate neoclassical monument. Somehow it also seemed dormant, its pale grey stones lukewarm, the courtyard’s air motionless in its enclosure between the surrounding buildings. The limited number of tickets meant that the cobbled yard was filled not with raucous rumble of an agitated crowd but with soft voices, conversations merging into a faint hum that ebbed and flowed as we made our way closer to the stage.

LJW: The crowd was sparsely dispersed allowing for both space and intimacy. Our evening began almost farcically with spontaneous purchases of plastic pint glasses of Prosecco that we haphazardly balanced on the cobbles. The opening act, ALA.NI, was exuberant and overwhelmingly talented, performing under a colourless and livid sky. The setting and the sound became a total juxtaposition of each other. The notes that woman’s mouth could produce were truly incomprehensible, as though a lark hid in her chest.

OL: ALA.NI even resembled a bird, perched on a tall stool, restless, rising every few minutes and then sitting down again, the movements of her arms in perfect synchrony with the motions of her voice—at times, she spread them almost wing-like as her songs rolled over our heads, melting into the warm July evening. Her voice was sweet like a lark’s, too: melancholic and joyful bluesy tunes, carefree almost, that captivated the audience who seemed to have been left wanting more as ALA.NI left the stage after her half-hour set.

As we waited for Clementine to appear on the stage, I talked and talked to Lara. People were moving around us, clouds of smoke puffed out into the air, empty plastic cups crackling under people’s feet. Time seemed to slow down, trapped in the viscous midsummer air.

When, at last, Benjamin Clementine came on stage, the crowd’s anticipatory hum suspended as if everyone held their breath at once: Benjamin Clementine seemed to glow with an otherworldly energy.

LJW: As he played his opening song the grey sky, once still and full, exploded into pink light, translucent streaks of colour darting across the sky. The atmosphere changed, tangibly, the subdued crowd stirred, galvanised with Clementine’s energy. When he sang, he exuded the sublime, he was more a being than a human.

OL: His lyrics, too, were imbued with the sublime. When ‘Adios’, a gripping song with dynamic chords and forceful, unyielding verses broke off into a surreal interlude, Clementine spoke of talking to angels—“When I’m on my journey, figuring things out, I do come across… / the angels, they come to me and they sing to me so beautifully”. I stood bewitched, convinced that the man on the stage, whose voice undulated so arrestingly, and whose hands fluttered over the piano’s keys so softly and tenderly and yet with such force, indeed has his songs whispered in his ears by angels.

LJW: It felt like he wasn’t human, but at the same time he was the most humane being present at the venue. We felt his humanity, his sanity. ‘London’ situated us perfectly in our surroundings, lifted high as we were by Clementine’s lilting notes yet feeling the floor under our feet as his words remained grounded, honest and unpretentious.

OL: He sang so plainly and so bluntly about quintessentially human feelings: the love and the hate he evoked in his songs were the same love and hate that people have felt since the beginning of humanity.

LJW: He seemed as though a dinosaur that crawled straight out of the earth, gazed intently at society, observing and absorbing human feeling, and taking his first observations to a piano. The tension was palpable during the song composed off the cuff, not on the set list: the song about the EU Referendum, the sense of being English, about being the ‘Black British Boy’. Communal breath was held (or perhaps that was just me) as Benjamin achieved the unthinkable; raising the subject of Brexit without alienating either 52 or 48 per cent of the population. As he questioned and crooned over the contradictions involved, relieving notes swam over the heads of his listeners.

OL: The lyrics were so simple, the song opened with: “To stay, or not to stay; to leave, or not to leave”—an honest musing over the decision that one had to make, stripped of the political arguments, of cunning dishonesty and the entangled web of polemics. “To stay,” sang Clementine, and then, pausing to shrug his shoulders, to stare blankly at the audience for a moment, “Or not to stay.”

His set lasted for over an hour, maybe an hour and a half, and closed with a song with no lyrics. When he announced that it would be the last one, and that it would involve no singing, the audience stood reluctant, disappointed perhaps by what we thought would be an underwhelming closure to a beautiful evening. Yet it was anything but underwhelming: as Clementine’s fingers swiftly moved over the piano keys, the instrument responded with a melody so anguished, so disconcerting and beautiful that once again I marvelled at his ability to evoke this powerful state of disquietude through his music. As the Heritage Orchestra joined in, everything—the music, the mellow night, the dark sky, Clementine’s ghost-like figure, the surrounding buildings—seemed to become music, pure melody.

LJW: The evening was unforgettable. Bodies en masse swayed as though blood was pumping through one artery, the heart of which was sitting at a piano on stage. The sound swelling and pulsating from an orchestra and the man at the piano felt completely contemporaneous; an instinctive evolution from the classical greats.